LONDON

THE STORY OF THE CITY

SOLIDLY encased and built into the wall of St. Swithin's Church in Cannon Street is a stone that tradition says is older than London itself. If that stone could speak, as many stones with ogams and Celtic inscriptions upon them have been made to do, it might begin the record for us, whose first signs we can barely distinguish. Even now LONDON STONE is a remarkable witness in the record of the city that lies about it. Together with London Bridge and London Wall, it forms a triad of ancient city landmarks, which helps to define the old place in the map and the original limits of the small town in the Thames marshes, destined to become a world's capital.

The tradition about London Stone, as retailed by Camden and others, is that it was the actual Roman milliarium, or central milestone, from which the outgoing roads and distances were measured, as they are from Charing Cross to-day. What rather bears this out is the fact that the older part of Cannon Street where it stood, although not at the present spot, was actually the eastern end of Watling Street, which carried the line of that great highway into the Roman citadel, and afterwards became the chief thoroughfare of the city that arose and clustered its houses on the same site. If before the Romans came, there was a British settlement here, Camden's suggestion that the stone first belonged to it is not altogether an unlikely one. The name of London, which comes from "Llyn" – lake or pool, and "din" town or stockaded settlement, the Welsh or British term for the place, takes us back to some pre-Roman use of what was undoubtedly a site of many natural advantages.

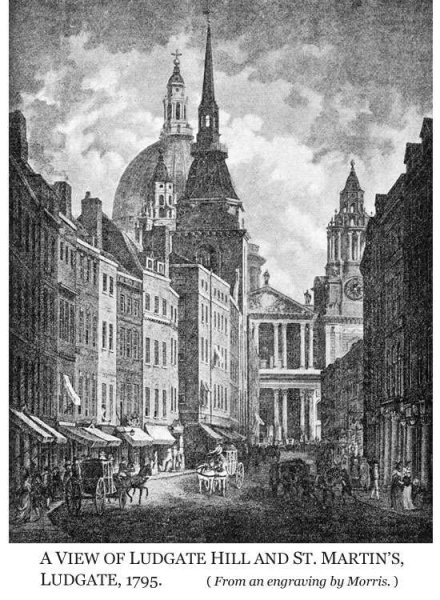

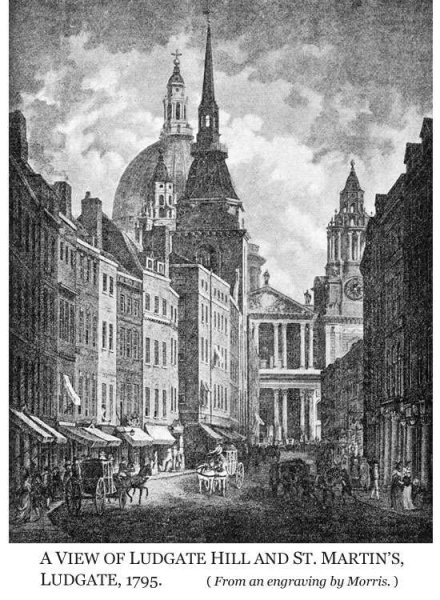

In those days the lower valley of the Thames was largely marshland, with many tributary small streams, ditches and mud-flats, which were covered with water at high tide. But the lie of the land about London favoured the collection of a large tidal pool at high-water below the small hills and the gravel banks marked for us by the rise of Ludgate Hill and the uplifted dome of St. Paul's. Here was the pool or llyn which took its name from the "din" – Welsh dinas, Irish dun, that rose above its waters. The town, so to call it, was a small, stockaded timber-built place, smaller than Troy itself. It may have had lake-dwellings as its nearest neighbours. It certainly had a track-way leading off westward, that the Romans adopted for the road known to us as Watling Street. They brought stone, where wood had been used; built a strong wall on the northern side, the origin of LONDON WALL; threw out a trestle-bridge over the river, the first LONDON BRIDGE, and placed, as their custom was, a Stone from which to measure their roads at the centre of their citadel, and at a spot near that where LONDON STONE stood for well over a thousand years. It stood however on the opposite side of the street to that where it is now ensconced, and well out in the road, outside the gutter or channel; so that it needed to be guarded and kept from cart-wheels by strong iron bars. A diagram of Roman London will show far better than any description the bounds of the town, its gates, walls, bridge and main citadel, of which Wallbrook was the western boundary.

It did not at once take the form shewn in the chart. The Roman citadel was built about 40-45 A.D. Another date we can fix approximately lies between 350 and 370, and it relates to the building of the wall round the suburbs. Hardly had it been completed, before it was attacked by the Britons from the north, and saved by the hand of Theodosius the elder.

The spade has unearthed from time to time many tell-tale relics of Londinium. The opening up of London Wall (the street so-called) by the Post Office, in order to lay telephone mains, in January, 1905, led to fresh discoveries. [*] These went to shew that the hidden and buried remains of the Wall were of very considerable extent at this point, confirming other accounts, that it was so well and soundly laid as to have provided foundation walls for many of the churches and mediaeval buildings and their later successors, including the Church of All Hallows. Most curious discovery of all was that during the Roman occupation of London, which began under promising conditions enough, the conditions changed for the worse. Brooks that had run clear became choked; and contrary to our accepted notions, the marshes seem to have gained on the surrounding ground. The Romans neglected the sanitation and drainage of their Augusta, with the result that under their rule, lasting some centuries, the city must have often suffered from fogs and malaria.

[* See the most interesting account contributed in June, 1906, by Mr. Philip Norman and Mr. F. W. Reader, the investigators, to the Society of Antiquaries. ]

But we have stayed long enough in Roman London. When it came to an end, there followed a doubtful period, with one entry in the Saxon chronicle to mark the fatal event, in 457, when Hengest defeated the Britons in Kent, and they in their terror fled to London. The next century, the sixth, is almost a blank. At the beginning of the seventh, we hear of Ethelbert giving a bishop's see at London to Mellitus. But there is not much to be gleaned of its life as a city, or a place of any growing civil importance, until Alfred's time. It was harried by the Danes again and again; every vestige of the Roman polity and civil law died out completely; and when Alfred seized it from the Danes in 884 or 885, he found in it only a rude camp, with the Roman Wall where it was not broken and patched with balks and timber still standing on the north; and with the Thames dammed and banked up on the south and south-west. By Alfred, the civil stamp and character of the London we know were first given to it. He was, says Mr. Loftie, its real founder. Some of the old divisions and boundaries made by him are still preserved. The old estates, or "sokes" of the rich citizens of his time decided the lines of the city wards, when they were formed. He made good, and in large part rebuilt, the old Wall. Markets sprang up, at East Cheap and West Cheap. New gates, like Ludgate and Westgate, were built and opened; and new roads were made, sometimes traversing and sometimes diverting the old. The early name, that had not been displaced by Augusta, was still maintained as Lundenbyrig or Londonborough. The central street in the Roman city, where London Stone stood, became Candlewick Street (Cannon Street). The government of the community became settled in the hands of those who really represented the commons. So the townsfolk, those who were freemen, had their folk-mote, their ward-mote, and their weekly "hustings" which had its various uses, akin in some ways to those of our county court. Then there was the knightenguild Stow's name; whose knights were really city merchants and city aldermen. The guild helps to remind us that the early citizens and merchants of London, during the Danish wars, had to be soldiers too, prepared to fight for their own, and to stand siege. But the Danes never took the city.

Æthelred's coward policy, however, showed the fear of the Danes, which led him to the fatal step of St. Brice's Day, November 13, 1002, when every Dane in England was ordered to be killed. Swegen's sister fell in the butchery, but he had his revenge, and became king. His son Cnut was chosen by the Danes after him. Cnut was a wise and a strong ruler; and the strength of London is shown by the way in which she resisted his power and strategy. He took Southwark, and may have cut off Westminster; London he could not take, in spite of the canal which took his ships above London Bridge. However, by the treaty between him and Edmund Ironside, London became his capital. A few Danish names still remain around London; but the city bears hardly any traces or memories of the Danish hold upon its walls. Those other Gallic northmen, the Normans, were to leave a different record. William the Conqueror had to recognise in his turn the strength of the City. He had to give it a Charter, by which its citizens held their rights and liberties: "And I will not endure that any man offer any wrong to you!" The Charter lies at the Guildhall. But William I. had his own sign-manual besides. The Norman argument was always a castle. He began to build the Tower of London on Tower Hill, just outside the walls.

The next charter was that of the first King Henry, which rather confirmed than altered the existing government of the city. The "hustings," the ward-mote, the folk-mote, were not interfered with. But to these, the Charter adds the new idea of London a corporation, although the old manors and "sokes," retain their rights. This was in 1100. The next step was that by which the portreeve was made into the mayor of the city, some ninety years later. The unifying of the city's government accompanies this change. Henry FitzAylwin of London Stone is the first mayor we can clearly distinguish, though not the first perhaps actually in office. His name reminds us of the fine old patrician stock from which London loved to recruit her aldermen and city officers in the middle ages.

![]()

![]()