Contents - Volume One

Chapter I

Cirencester – Source of the Thames – Kemble – Ashton Keynes – Cricklade – St. Augustine’s Well

Chapter II

Castle Eaton – Kempsford – By the Thames and Severn Canal to Inglesham

Round House – Lechlade – Fairford – Eaton Hastings Weir – Kelmscott –

Radcot Bridge

Chapter III

Great Faringdon – Buckland – Bampton-in-the-Bush – Cote – Shifford

Chapter IV

Harvests of the Thames: Willows, Osiers, Rushes

Chapter V

New Bridge, The Oldest on the Thames – Standlake – Gaunt’s House – Northmoor – Stanton Harcourt – Besselsleigh

Chapter VI

Cumnor, and the Tragedy of Amy Robsart

Chapter VII

Wytham – The Old Road – Binsey and the Oratory of St. Frideswide – The

Vanished Village of Seacourt – Godstow and “Fair Rosamond” – Medley –

Folly Bridge

Chapter VIII

Iffley, and the Way Thither – Nuneham, in Storm and in Sunshine

Chapter IX

Abingdon

Chapter X

Sutton Courtney – Long Wittenham – Little Wittenham – Clifton Hampden – Day’s Lock and Sinodun

Chapter XI

Dorchester – Benson

Chapter XII

Wallingford – Goring

Chapter XIII

Streatley – Basildon – Pangbourne – Mapledurham – Purley

Contents - Volume Two

Chapter I

Sonning – Hurst, “In the County of Wilts” – Shottesbrooke – Wargrave

Chapter II

Henley – The Bridge and its Keystone-Masks – Remenham – Hambleden – Medmenham Abbey and The “Hell Fire Club” – Hurley – Bisham

Chapter III

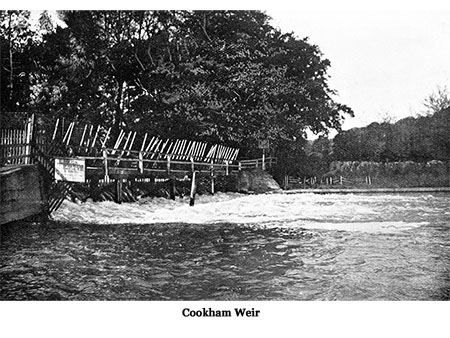

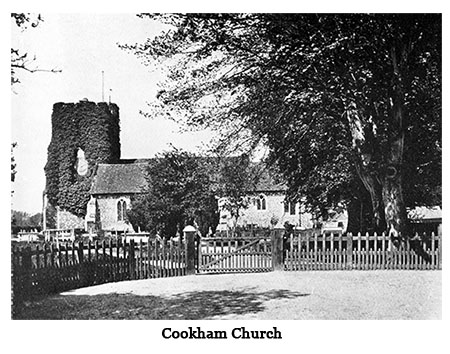

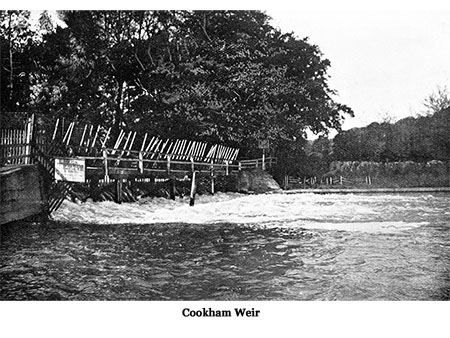

Great Marlow – Cookham – Cliveden and its Owners – Maidenhead

Chapter IV

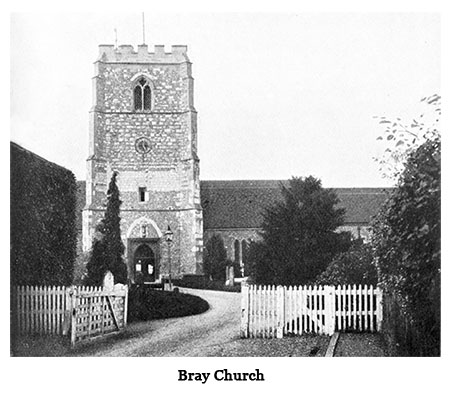

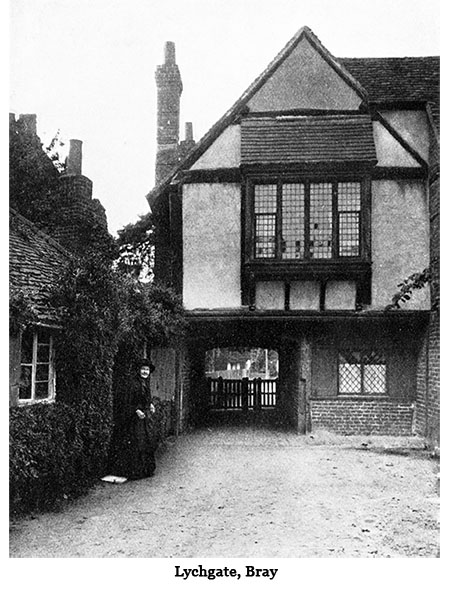

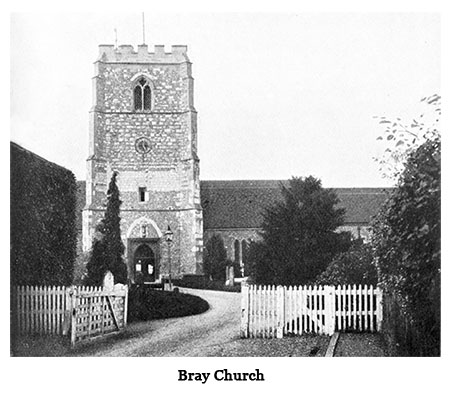

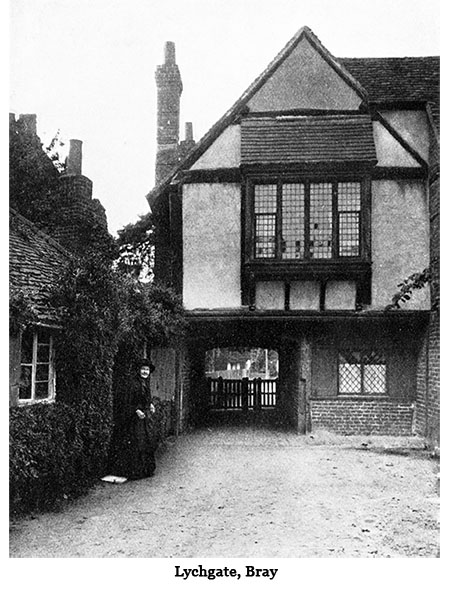

Bray and its Famous Vicar – Jesus Hospital

Chapter V

Ockwells Manor-House – Dorney Court – Boveney – Burnham Abbey

Chapter VI

Clewer – Windsor – Eton and its Collegians – Datchet Langley and the Kederminsters

Chapter VII

Datchet – Runnymede – Wraysbury – Horton and its Milton Associations –

Staines Moor – Stanwell – Laleham and Matthew Arnold – Littleton

Chertsey – Weybridge – Shepperton

Chapter VIII

Coway Stakes – Walton-on-Thames – The River and the Water Companies – Sunbury – Teddington – Twickenham

Chapter IX

Petersham

Chapter X

Isleworth – Brentford and Cæsar’s Crossing of the Thames

Chapter XI

Strand-on-the-Green – Kew – Chiswick – Mortlake – Barnes

Chapter XII

Putney – Fulham Bridge – Fulham

Introductory

The Thames we all know intimately, for the river was

discovered by the holiday-maker in the ’seventies of the nineteenth

century; but we do not all know the villages of the Thames Valley, and

it was partly to satisfy a long-cherished curiosity on this point, and

partly to make holiday in some of the little-known nooks yet remaining,

that this tour was undertaken. To one who lives, or exists, or resides

– the reader is invited to choose his own epithet – beside the lower

Thames, there must needs at times come a longing to know that upper

stream whence these mighty waters originate, to find that fount where

“Father Thames” starts forth in hesitating, infantile fashion; to seek

that spot where the stream, instead of flowing, merely trickles. To

such an one there comes, with every recurrent spring, the longing to

penetrate to the Beyond, away past where the towns and villages, the

water-works and breweries cluster thickly beside the river-banks; above

the town of Reading, the Biscuit Town, and town of sauce and seeds;

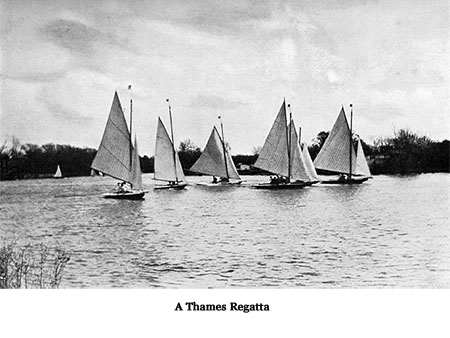

beyond the fashionable summer scene of Henley Regatta, and past the

city of Oxford, to the Upper River and its unconventionalised life.

When spring comes and wakes the meadows with

delight, and the osiers and the rushes again feel life stirring in

their dank roots, the old schoolboy feeling of curiosity, of mystery,

of a desire for exploration, springs anew. You walk down, it may be, to

some slipway or draw-dock by Richmond or Teddington, or wander along

those shores contemplating the high-water-marks left by the late winter

floods, which not even the elaborate locking of the river seems able to

prevent; and observing the curious line of refuse of every description

brought down by the waters, and now left, high and dry, a matted mass

of broken rushes, water weeds, twigs, string and the like, marvel at

the wealth of corks that displays itself there. Children have been

known to make expedition towards the distant hills, seeking that place

where the rainbow touches the ground; for the sly old legend tells us

that on the spot where the glorious bow meets the earth there lies

buried a crock of gold. An equally speculative quest would be to fare

forth and seek the Place whence the Corks Come. There (not for

children, but for “grown-ups”) should be, you think, the Land of

Heart’s Desire.

There are, I take it, three chief things that the

world of men most ardently wishes for. An unregenerate man’s first

desires are to wealth, to a woman, and to a drink; or, in the words

attributed to Martin Luther:

Who loves not woman, wine, and song,

He is a fool his whole life long;

and the valley of the Thames, from Oxford to Richmond, would seem, by

the evidence of these millions of corks of all kinds, to be a place

flowing with champagne, light wines, all kinds of mineral waters, and

bottled beers.

Corks, rubber rings from broken

mineral-water bottles, and big bungs that hint of two- or three-gallon

jars, abound; these last telling in no uncertain manner of the

magnificent thirsts inspired among anglers who sit in punts all day

long, and do nothing but keep an eye on the float, and maintain the

glass circulating.

A thirsty person wandering by these bestrewn

towing-paths must sigh to think of the exquisite drinks that have gone

before, leaving in this multitude of corks the only evidence of their

evanescent existence. Shall we not seek it, this land of the foaming

champagne, that comes creaming to the brim of the generous glass; shall

we not hope to locate those shores, far or near, where the bottled

Bass, poured into the ready tumbler, tantalises the parched would-be

drinker of it in the all-too-slowly-subsiding mass of froth that lies

between him and his expectant palate? Shall we not, at least if we be

of “temperance” leanings, quaff the cool and refreshing “stone-bottle”

ginger-beer; or, failing that, the skimpy and deleterious

“mineral-water” “lemonade” that is chiefly compounded of sugar and

carbonic-acid gas, and blows painfully and at high-pressure through the

titivated nostrils? Shall we not — but hold there! Waiter, bring me –

what shall it be? – an iced stone-bottle ginger!

That was the brave time, the golden age of the

river, when, rather more than a generation ago, the discovery of the

Thames as a holiday haunt was first made. The fine rapture of those

early tourists, who, deserting the traditional seaside lounge for a

cruise down along the placid bosom of the Thames, from Lechlade to

Oxford, and from Oxford to Richmond, were (something after the Ancient

Mariner sort) the first to burst into these hitherto unknown reaches,

can never be recaptured. The bloom has been brushed from off the peach

by the rude hands of crowds of later visitors. The waterside inns, once

so simple under their heavy beetling eaves of thatch, are now modish,

instead of modest; and Swiss and German waiters, clothed in deplorable

reach-me-down dress-suits and lamentable English of the

Whitechapel-atte-Bowe variety, have replaced the neat-handed – if

heavy-footed – Phyllises, who were almost in the likeness of those who

waited upon old Izaak Walton, two centuries and a quarter ago.

To-day, along the margin of the Thames below

Oxford, some expectant mercenary awaits at every slipway and

landing-place the arrival of the frequent row-boat and the plenteous

and easily-earned tip; and the lawns of riparian villas on either hand

exhibit a monotonous repetition of “No Landing-Place,” “Private,” and

“Trespassers Prosecuted” notices; while side-channels are not

infrequently marked “Private Backwater.”

All the villages immediately giving upon the stream

have suffered an equally marked change, and have become

uncharacteristic of their old selves, and converted into the likeness

of no other villages in this our England, in these our times. There is,

for example, a kind of theatrical prettiness and pettiness about

Whitchurch, over against Pangbourne; and instead of looking upon it as

a real, living three-hundred-and-sixty-five-days-in-the-year kind of

place, you are apt to think of what a pretty “set” it makes; and, doing

so, to speak of its bearings in other than the usual geographical terms

of east and west, north and south; and to refer to them, indeed, after

the fashion of the stage, as “P.” or “O.P.” sides.

But if we find at Whitchurch a meticulous neatness,

a compact and small-scale prettiness eminently theatrical, what shall

we say of its neighbour, Pangbourne, on the Berkshire bank of the

river? That is of the other modern riverain type: an old village

spoiled by the expansion that comes of being situated on a beautiful

reach of the Thames, and with a railway station in its very midst.

Detestable so-styled “villas” and that kind of shops you find nowhere

else than in these Thames-side spots, have wrought Pangbourne into

something new and strange; and motor-cars have put the final touch of

sacrilege upon it.

Perhaps you would like to know of what type the

typical Thames-side village shop may be, nowadays? Nothing easier than

to draw its portrait in few words. It is, to begin with, inevitably a

“Stores,” and is obviously stocked with the first object of supplying

boating-parties and campers with the necessaries of life, as understood

by campers and boating-parties. As tinned provisions take a prominent

place in those holiday commissariats, it follows that the shop-windows

are almost completely furnished with supplies of tinned everything,

festering in the sun. For the rest, you have cheap camp-kettles,

spirit-stoves, tin enamelled cups and saucers, and the like utensils,

hammocks and lounge-chairs.

Thus the modern riverside village is unpleasing to

those who like to see places retain their old natural appearance, and

dislike the modern fate that has given it a spurious activity in a

boating-season of three months, with a deadly-dull off-season of nine

other months every year. We may make shift to not actively dislike

these sophisticated places in summer, but let us not, if we value our

peace of mind, seek to know them in winter; when the sloppy street is

empty, even of dogs and cats; when rain patters like small-shot on the

roof of the inevitable tin-tabernacle that supplements the

over-restored, and spoiled, parish church; and when the roar of the

swollen weir fills the air with a thudding reverberance. Pah!

The villas, the “maisonettes” are empty: the

gardens draggle-tailed; the “Nest” is “To Let”; the “Moorings” “To be

Sold”; and a general air of “has been” pervades the place, with a

desolating feeling that “will again be” is impossible.

But let us put these things behind us, and come to

the river itself; to the foaming weir under the lowering sky, where

such a head of water comes hurrying down that no summer frequenter of

the river can ever see. There is no dead, hopeless season in nature;

for although the trees may be bare, and the groves dismantled, the

wintry woods have their own beauty, and even in mid-winter give promise

of better times.

But along the uppermost Thames, from Thames Head to

Lechlade and Oxford, the waterside villages are still very much what

they have always been. All through the year they live their own life.

Not there do the villas rise redundant, nor the old inns masquerade as

hotels, nor chorus-girls inhabit at week-ends, in imitative simplicity.

A voyage along the thirty-two miles of narrow, winding river from

Lechlade to Oxford has no incidents more exciting than the shooting of

a weir, or the watching of a moor-hen and her brood.

Below Oxford, we have but to adventure some little

way to right or left of the stream, and there, in the byways (for main

roads do not often approach the higher reaches of the river), the

unaltered villages abound.

Abingdon

Abingdon, some three miles distant, now claims attention;

and a good deal of leisured attention is its due. That pleasant and

quietly-prosperous old town is one of those fortunate places that have

achieved the happy middle course between growth and decay, and thus are

not ringed about with squalid, unhistorical, modern additions. Its

population remains at about 6,500, and therefore it is not, although

possessing from of old a Mayor and Corporation, a town at all in the

modern sense. Thus shall I shift to excuse myself for including it in

these pages. In these days of great populations we can scarce begin to

think of a place of fewer than ten thousand inhabitants, as a “town” at

all.

The origin of Abingdon, whose very name

is said to mean “the Abbey town,” was purely ecclesiastical, for it

came into existence as a dependency of the great Abbey founded here in

the seventh century. Legends, indeed, tell us of an earlier Abingdon,

called “Leavechesham,” in early British times, and make it even then an

important religious centre and a favourite residence of the kings of

Wessex, but they – the legends and the kings alike – are of the

vaguest.

Leland, in the time of Henry the Eighth,

wrote of the town: “It standeth by clothing,” and it did so in more

than one sense, for it not only made cloth, but a great deal of traffic

between London and Gloucester, Stroud, Cirencester, and other great

West of England clothing centres, came this way, and had done so ever

since the building of Abingdon (or Burford, i.e. Boroughford)

bridge and the bridge at Culham Hithe in 1416, had opened a convenient

route this way. The town owed little to the Abbey, for the proud mitred

abbots, who here ruled one of the wealthiest religious houses in

England, and sat in Parliament in respect of it, were not concerned

with such common people as tradesfolk, and did not by any means

encourage settlers. They trafficked only with the great, and aimed at

keeping Abingdon select. From quite early times they had adopted this

attitude: perhaps ever since William the Conqueror had entrusted to the

monastery the education of his son Henry, afterwards Henry the First –

an education so superior that, by reason of it, Henry the First lives

in history as “Beauclerc.”

It was a

highly-prosperous Abbey, and smelt to heaven with pride, and had a very

bad reputation for tyrannical dealings with those who had managed to

settle here. The Abbot refused to allow the people to establish a

market, and in 1327 the enmity thus caused broke out into riot. From

Oxford there came the Mayor and a number of scholars, to help the

people of Abingdon in their quarrel, and part of the Abbey was burnt,

its archives destroyed, and the monks driven out. But this was a sorry,

and merely a temporary, victory; for the Abbot procured powerful

assistance and regained his place, and twelve of the rioters were

hanged.

The scandalous arrogance and state of the

Abbots of Abingdon aroused the wrath of Langland, a monk himself, but

one of liberal views, who some few years later wrote that prophetic

work, The Vision of Piers Plowman, in which the downfall of this great Abbey is directly and specifically foretold:

“Eke ther shal come a kyng,

And confesse yow religiouses,

And bete you as the Bible telleth

For brekynge of your rule.

And thanne shal the abbot of Abyngdone.

And al his issue for evere,

Have a knok of a kyng,

And incurable the wounde.”

When the Abbey was suppressed in 1538, its annual income

was £1,876 10s. 9d., equal to about £34,000, present value.

With the disappearance of the Abbey, the

town of Abingdon grew, and continued to prosper by clothing and by

agriculture until the opening of the railway era. When the Great

Western Railway was originally planned, in 1833, it was intended to

take it through Abingdon, instead of six miles south, as at present,

and to make this, instead of Didcot, the junction for Oxford. But

Abingdon was strongly opposed to the project, and procured the

diversion of the line, and so it remains to this day an exceedingly

awkward place to reach or to leave, by a small branch railway. It has

thus lost, commercially, to an incalculable degree, but in other ways –

in the preservation of beauty and antiquity – has gained, equally

beyond compute.

An architect might find some stimulating

ideas communicated to him by the quaint and refined detail observable

in many of the old houses. There is, among other curious houses near

the Market House, the “King’s Head and Bell,” in an odd classic

convention.

Of the great Abbey church nothing is left. The townsfolk

had such long-standing and bitter grievances against the Abbey that

they must have rejoiced exceedingly when the fat and lazy monks were at

last cast out upon the world; and they seem to have revelled in

destruction. The Abbey precincts are now largely built over; but, such

as they are to-day, they may be found by proceeding out of the Market

Place, past St. Nicholas’ church, and through the Abbey gateway, now

used as part of the Town Hall, and restored, but once serving as a

debtors’ prison.

Here a mutilated and greatly time-worn

Early English building will be found, with a vaulted crypt, and two

rooms above. To this has been given the (probably erroneous) name of

the “Prior’s House.” Its curiously stout Early English chimney, with

lancet-headed openings, under queer little gables, is a landmark not

easily missed The successor of the original Abbey Mill is itself very

picturesque. Adjoining is the long, two-storeyed building often styled

the “Infirmary,” and sometimes the “Guest House”; perhaps having

partaken of both uses. It can only have been used for humble guests, or

patients, for it is merely a rough-and-ready wooden building, rather

barn-like, divided into dormitories.

The charming little Norman and Perpendicular church of St.

Nicholas has been very severely dealt with by “restoring” hands, but

its quaintness and charm appear indestructible. An especially peculiar

feature of the altogether unconventional West front is seen in the

curious little flat-headed window under a gable roof to the north side

of the tower, giving a curiously semi-domestic appearance to the

church. The windows light a staircase turret, which is perhaps the

remaining part of some priest’s residence formerly attached to the

church.

But, far or near, the chief feature of

Abingdon is St. Helen’s church, whose tall and graceful spire has the

peculiar feature of being built in two quite distinctly different

angles: the lower stage much less acute than the upper. It is what

architects call an “entasis.” A band of ornament marks the junction of

the two stages. This spire is of the Perpendicular period, built upon

an Early English tower. The rest of this exceptionally large and

beautiful church, which has the peculiarity of being provided with a

nave and four aisles, is Perpendicular. It should be noted that what

are now the two extra aisles were originally built by the town guilds,

as chapels. The five aisles form a noble vista, looking across the

church. They are named, from north to south, Jesus Aisle, Our Lady’s,

St. Helen’s, St. Catharine’s, and Holy Cross. The great breadth of the

church originated a local saying, by which either of alternative

courses of any action, supposed to have little to choose between them,

may often be heard referred to as “That’s as broad as it’s long, like

St. Helen’s church.”

Brasses and monuments of Abingdon’s old merchants and

benefactors are numerous: among them this curious inscription to

Richard Curtaine, 1643:

“Our curtaine in this lower press

Rests folded up in Natur’s dress;

His dust perfumes this urn, and he

This towne with liberalitie.”

Here, too, is the tomb of John Roysse, citizen of London,

and mercer, who founded here “Roysse’s Free School,” and died in 1571.

The slab covering his tomb came from his London garden.

The town is singularly rich in old and

interesting almshouses, the churchyard being enclosed on three sides by

various charitable foundations of this kind. Of these the oldest and

most remarkable is the almshouse founded about 1442 by the Guild of

Holy Cross, and refounded after the Reformation, in 1553, as Christ’s

Hospital, by Sir John Mason, an Abingdon worthy who rose from the

humblest beginnings to be Ambassador to the French Court, and

Chancellor of the University of Oxford. The chief feature of Christ’s

Hospital, as regards its front, is the long half-timber cloister, with

no fewer than one hundred and sixty little openings in the woodwork,

looking out to the churchyard. A picturesque porch projects midway, and

from the steep roof rises a quaint lantern, crowned with cupola and

vane. Old black-letter and other texts and paintings cover the walls of

the cloister. Under the lantern is the hall, or council-chamber, an

old-world room with a noble stone-mullioned bay window looking out upon

the almshouse gardens in the rear. In this window are set forth the

arms of benefactors towards the institution, and their portraits

further adorn the walls, together with a curious contemporary account

of the buildings of Abingdon and Culham Hithe bridges. As the value of

endowments increased, so the buildings of Christ’s Hospital have been

from time to time added to; and in addition there are Twitty’s and

Tomkins’s almshouses. A gable-end of Christ’s Hospital abuts upon St.

Helen’s Quay, on the river-side, with inscriptions curiously painted

under protecting canopies: “God openeth His hand and filleth all things

living with plenteousness; be we therefore followers of God as dear

children. 1674”; and “If one of thy Brethren among you be poore within

any of thy Gates in thy land which the Lord God giveth thee, thou shalt

not harden thy heart, nor shut thine hand from thy poor Brother. 1674.”

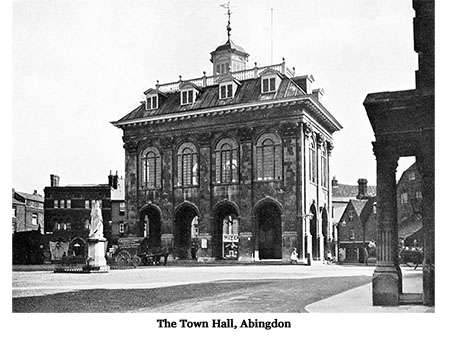

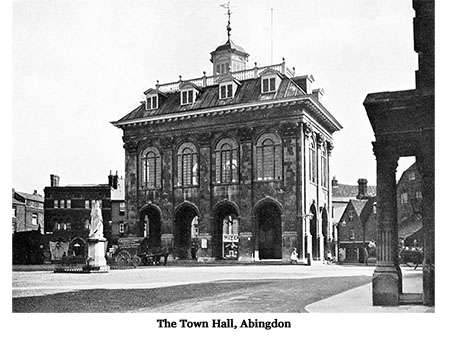

Abingdon is full of noble old buildings, both of a public

and a private character, and prominent among them must be reckoned the

imposing Market House. There is nothing else quite like it, in style or

in dignity, in England, and it is not too much to say that it would, by

itself, ennoble any town. It was built 1678-84, and followed in plan

the old conventional lines of such buildings: i.e. an open,

arcaded ground floor, supporting an upper storey; but in design it is

one of the purest examples of revived classic architecture in the land.

The upper storey in this case was intended for use as a sessions-house.

The design has been variously attributed to Inigo Jones,

to Webb, his successor in business, or to Sir Christopher Wren, without

any other evidence than that it partakes of the known style of all

these. But Inigo Jones died in 1652, and Webb in 1674, and so they are

both out of the question. There are at present time in private

possession at Abingdon a few old documents, preserved by merest chance,

which abundantly prove who built the Market House, if not precisely who

designed it. They detail payments made to Christopher Kempster, whom we

have met earlier in these pages. He was, or at this time had been,

clerk-of-works and master-mason to Wren, in his rebuilding of St.

Paul’s Cathedral and the City churches, and afterwards retired to

Burford, where he owned quarries. He would have been forty-eight years

of age at the time when this Market House was begun. Unless we are

prepared to assume him a transcendental clerk-of-works and a very

Phoebus of a master-mason, it seems scarce likely that he designed, as

well as built, this exceptionally fine structure; and the inference

therefore to be drawn is that he induced Wren to sketch out the design

and built to it, either with or without the supervision of that great

architect.

Great Marlow – Cookham – Cliveden and its Owners – Maidenhead

Marlow town is well within sight from Bisham. It is very

much more picturesque at a distance than it is found to be when arrived

near at hand; and the graceful stone spire of its church is found to be

really a portion of a very clumsy would-be Gothic building erected in

the Batty-Langley style, about 1835. A fine old Norman and later

building was destroyed to make way for this; and now the present church

is in course of being replaced, in sections, by another, as the funds

to that end come in. An interesting monument in the draughty lobby of

the present building commemorates Sir Myles Hobart, of Harleyford, who,

when Member of Parliament for Marlow, in 1628, distinguished himself by

his sturdy opposition to the King’s illegal demands; and with his own

hands, on a memorable occasion, locked the door of the House of

Commons, to secure the debate on tonnage and poundage from

interruption. For this he suffered three years’ imprisonment.

The monument, shamefully “skied” on the

wall of this lobby, was removed from the old church. Hobart met his

death in 1652 by accident, the four horses in his carriage running away

down Holborn Hill, and upsetting it. A curious little sculpture on the

lower part of the monument represents this happening, and shows one of

the wheels broken. The monument is further interesting as having been

erected by Parliament; the first to be voted of any of a now lengthy

series.

In the vestry, leading out of this lobby, among a number

of old prints hung round the walls, is an old painting of a naked boy,

with bow and arrow, his skin spotted all over, leopard-like, with brown

spots. This represents the once-famous “Spotted Negro Boy,” a supposed

native of the Caribbean Islands, who formed a very attractive feature

of Richardson’s Show in the first decade of the nineteenth century. We

shall probably not be far wrong in suspecting Mr. William Richardson of

a Barnum-like piece of showman humbug in putting this child forward as

a “Negro Boy.” The boy, one cannot help thinking, was sufficiently

English, but was a freak, suffering from that dreadful skin disease, ichthyosis serpentine. He lies buried in the churchyard.

There are a few literary associations in Marlow town, and

by journeying from the riverside and along the lengthy High Street, to

where that curious building, the old Crown Hotel, stands, facing down

the long thoroughfare, you may come presently to the houses that

enshrine them. Turning here to the left you are in West Street,

otherwise the Henley road, and passing the oddly named “Quoiting

Square,” there in the quaintly pretty old Albion House next door to the

old Grammar School, lived Shelley in 1817. A tablet on the coping, like

a tombstone, records the fact. He divided his time between writing the Revolt of Islam,

and in visiting the then degraded, poverty-stricken lower orders of the

town and talking nonsense to them. As no report of his conversations

survives, we can only wonder if they were as bad as the turgid nonsense

of that poem. Does any one nowadays ever read the Revolt of Islam,

or know why Islam did it, or if, in so doing, it succeeded? In short,

it will take a great deal of argument to convince the world that

Shelley was not the Complete Prig of his age, and in truth the house is

much more delightful and interesting for itself than for this

association. In Shelley’s time it was very much larger than now, and

comprised the two or three other small houses which have been divided

from it.

At “Beechwood” lived Smedley, author of Frank Fairleigh and Valentine Vox,

and on the Oxford road resided G. P. R. James, romantic novelist, whose

romances were said, by the satirists of his methods, generally to

commence with some such formula as–

“As the shades of evening were falling upon Deadman’s Heath, three horsemen might have been observed,” etc.

Marlow Weir is, to oarsmen not intimately acquainted with

this stretch of the river, the most dangerous on the Thames, so it

behoves all to give the weir-stream a wide berth in setting out again

from Marlow Bridge; that suspension-bridge, built in 1831, which, like

the neighbouring church, looks its best at a considerable distance.

River-gossipers will never let die that old satirical query, “Who ate

puppy-pie under Marlow Bridge?” the taunt being directed, according to

tradition, against the bargees of long ago, who, accustomed to raid the

larder of a waterside hotel at Marlow, were punished admirably by the

landlord, who, having drowned a litter of puppies, caused them to be

baked in a large pie, and the pie to be placed where it could not fail

to attract the attention of the raiders, who stole it, and consumed it

with much satisfaction, under the bridge.

Two miles below Marlow, past Spade Oak

ferry, is Bourne End, on the Buckinghamshire side; a modern collection

of villas clustered around a delightful backwater known as Abbotsbrook,

and by the outlet of the river Wye – the “bourne” which ends here and

gives rise to the place-name. It comes down from Wycombe, to which also

it gives a name, and Loudwater.

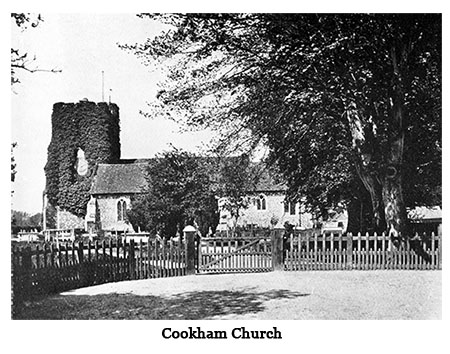

Cookham now comes into view, on the

Berkshire shore. Here the village is grouped around a village green;

rather a sophisticated green in these days, and combed down and brushed

up smartly since those times when Fred Walker began his career. Then

the geese and ducks roamed about that open space, and in the unspoiled

village; and old gaffers in smock-frocks and wonderful beaver-hats with

naps on them as thick as Turkey carpets sat about on benches in front

of old inns, and smoked extravagantly long churchwarden-pipes. The old

gaffers have long since gone, and the Bel and the Dragon Inn has become

a hotel, and Walker is dead and already an Old Master. You may see his

grave in the churchyard, and read there how he died, aged thirty-five,

in 1875. There is, in addition, a portrait-medallion within the church

itself, which gives him a half-drunken, half-idiotic expression that

one hopes did not really belong to him.

Behind the organ a curious mural monument to Sir Isaac

Pocock, Bart., dated 1810, represents the baronet “suddenly called from

this world to a better state, whilst on the Thames near his own house.”

He is seen in a punt, being caught while falling by a personage

intended to represent an angel, in tempestuous petticoats, while a

puntsman engaged in poling the craft looks on, in very natural surprise.

From Cookham, where the lock is set amid wooded scenery, the transition to Cliveden is easy.

Clieveden, Cliefden, Cliveden you may suit individual

taste and fancy in the manner of spelling looks grandly from the

Buckinghamshire heights down on to the Berkshire levels of Cookham and

Ray Mead. Perhaps the most beautiful view of all is from Cookham Lock.

Ray Mead, that was until twenty years ago just a mead – a beautiful

stretch of grass-meadows is now the name of a long line of villas with

pretty frontages and gardens, but deplorable names – “Frou-Frou,” “Sans

Souci,” and the like and inhabited, often enough, as one might suppose

by the Frou-frous of musical comedy and their admirers.

Cliveden, sometime “bower of wanton

Shrewsbury and of love,” and now residence of the highly respectable

and remarkably wealthy Mr. William Waldorf Astor, looks in lordly

fashion upon such. With the proceeds of his New York rent-roll that

Europeanised American in 1890 purchased the historic place from the

first Duke of Westminster, and has resided here and at other of his

English seats ever since. Those who are conversant with American

newspapers are familiar with the scream every now and again raised

against this and other examples of American money being taken and spent

abroad. The spectacle of that bird of prey raging because of the

dollars riven from it is amusing, but the situation may become

internationally serious yet, for when some great financial crisis

arises in the United States and money is scarce, it is quite to be

expected that the question of the absentee landlords will become acute,

and talk of super-taxing and expropriation be heard. I believe this

particular Astor is now a naturalised Englishman, and I don’t suppose

him to be the only one. Suppose, then, that the Government of the

United States at some future time seized the property of such, how

would the international situation shape?

Cliveden, when it was thus sold, had not

been long in the hands of the Grosvenor family; having been, a

generation earlier, the property of the Duke of Sutherland, for whom

the present Italianate mansion was built by Sir Charles Barry in 1851,

following upon a fire which had destroyed the older house, for the

second time in the history of the place. The original fire was in 1795.

In the mansion then destroyed the air of “Rule, Britannia,” had first

been played in 1740, as an incidental song in Thomson’s masque of Alfred, the music composed by Dr. Arne.

Boulter’s Lock, the water-approach to Maidenhead, is the

busiest lock on the Thames, and now busier on Sundays than on any other

day. How astonishingly times have changed on the river may be judged

from an experience of the late Mr. Albert Ricardo, who died at the

close of 1908, aged eighty-eight. He lived at Ray Mead all his long

life, and was ever keen on boating. When he was a comparatively young

man, he brought his skiff round to the lock one Sunday. His was the

only boat there, and he was addressed in no measured terms by a man who

indignantly asked him if he knew what day it was, and telling him, in

very plain language, his opinion of a person who used the river on

Sunday. Since then a wave of High Churchism and irreligion (the two

things are really the same) has submerged the observance of the

Sabbath, and aforetime respectable persons play golf on the Lord’s Day.

A quaint incident, one, doubtless, of

many, comes to me here, in considering Boulter’s Lock, out of the dim

recesses of bygone reading.

Says Mr. G. D. Leslie, R.A., in his entertaining book, Our River:

“I came through the lock once simultaneously with H.R.H. the Duke of

Cambridge. He was steering the boat he was in, and I am sorry to say I

incurred his displeasure by accidentally touching his rudder with my

punt’s nose.”

Oh dear!

He does not tell us what H.R.H. said on this historic occasion;

but a knowledge of the Royal Duke’s fiery temper and of his ready and

picturesque way of expressing it leads the present writer to imagine

that his remarks were of a nature likely to have been hurtful to the

self-respect of the Royal Academician. But it is something – is it not?

– to be able to record, thus delicately, by implication, that one has

been vigorously cursed by a Royal Duke. Not to all of us has come such

an honour!

And now we come to Maidenhead town, a town of 12,980

persons, and yet a place that was, not so very long ago, merely in the

parishes of Cookham and Bray. (It was created a separate civil parish

only in 1894.) Its growth, originally due to its situation on that old

coaching highway, the Bath road (which is here carried across the river

by that fine stone structure, Maidenhead Bridge, built in 1772, to

replace an ancient building of timber), has been further brought about

by the modern vogue of the river, and by the convenience of a railway

station close at hand.

“Maidenhead” is, according to some views,

the “mydden hythe,” the “middle wharf” between Windsor and Marlow.

Camden assures us that the name derived from “St. Ursula” one of the

eleven thousand virgins murdered at Cologne. But St. Ursula and the

eleven thousand maiden martyrs, who are said to have been shot to death

with arrows, A.D. 451, are as entirely mythical as Sarah Gamp’s “Mrs. Harris.”

But there is plenty choice in the origin of this

place-name. There are those who plump for “magh-dun-hythe,” the wharf

under the great hill (of Cliveden). The place is found under quite

another name in Domesday Book. There it is “Elenstone,” or “Ellington.”

It is first styled “Maydehuth” in 1248; and it has been thought that

the name is equivalent to “new wharf”; the wharf, or its successor,

mentioned by Leland in 1538 as the “grete warfeage of tymbre and

fierwood.”

We need not, perhaps, expend further

space upon the town of Maidenhead, for it is almost entirely modern.

Its fine stone bridge has already been mentioned, and another, and a

very different, type of bridge, a quarter of a mile below it, now

demands attention.

Maidenhead Railway Bridge, completed in

1839, one of those greatly daring works for which the Great Western

Railway’s original engineer, Isambard Kingdom Brunel, was famous, is

the astonishment of all who behold it. Crossing the river in two spans,

each of 128 feet, the great elliptical brick arches are the largest

brickwork arches in the world, and of such flatness that it seems

scarcely possible they can sustain their own weight, even without the

heavy burden of trains running across. Maidenhead Railway Bridge

astonishes me infinitely more than the great bridge across the Forth,

or any other engineering feats. Yet sixty years have passed, and the

bridge not only stands as firmly as ever, but nowadays sustains the

weight of trains and engines more than twice as heavy as those

originally in vogue. Moreover, in the doubling of the line, found

necessary in 1892, the confidence of the Company was shown by their

building an exact replica of Brunel’s existing bridge, side by side

with it. Yet the original contractor had been so alarmed that he

earnestly begged Brunel to allow him to relinquish the contract, and

although the engineer proved to him, scientifically, that it must

stand, he went in fear that when the wooden centreing was removed the

arches would collapse. A great storm actually blew down the centreing

before it was proposed to remove it, but the bridge stood, and has

stood ever since, quite safely. It cost, in 1839, £37,000 to build.

Combined Index

Abingdon – Vol. I Ch. 5, Ch. 9

Ashton Keynes – Vol. I Ch. 1

Augustine, St. – Vol. I Ch. 1

Bablockhythe – Vol. I Ch. 6

Bampton – Vol. I Ch. 3

Barnes – Vol. II Ch. 11

Basildon – Vol. I Ch. 13

Benson – Vol. I Ch. 11

Besselsleigh – Vol. I Ch. 5

Beverley Brook – Vol. II Ch. 12

Binsey – Vol. I Ch. 7

Bisham – Vol. II Ch. 2, Ch. 9

Bourne End – Vol. II Ch. 3

Boveney – Vol. II Ch. 6

Bray – Vol. II Ch. 4

Brentford – Vol. II Ch. 10

Brightwell – Vol. I Ch. 11

Brightwell, Salome – Vol. I Ch. 11

Buckland – Vol. I Ch. 3

Burford – Vol. I Ch. 2

Burlington – Vol. II Ch. 11

Burnham Abbey – Vol. II Ch. 5

Buscot – Vol. I Ch. 2

Cæsar, Julius – Vol. II Ch. 8, Ch. 10

Cambridge, H.R.H. Duke of – Vol. II Ch. 3

Carfax Conduit – Vol. I Ch. 8

Castle Eaton – Vol. I Ch. 2

Caversham – Vol. I Ch. 13

Charney Brook – Vol. I Ch. 3

Chertsey – Vol. II Ch. 7

Chiswick – Vol. II Ch. 11

Cholsey – Vol. I Ch. 13

Churn, River – Vol. I Ch. 1, Ch. 2

Cirencester – Vol. I Ch. 1

Clanfield – Vol. I Ch. 2

Clewer – Vol. II Ch. 6

Clifton Hampden – Vol. I Ch. 10

Cliveden – Vol. II Ch. 3

Coln, River – Vol. I Ch. 2

Colne, River – Vol. II Ch. 7

Cookham – Vol. II Ch. 3

Cote – Vol. I Ch. 3

Coway Stakes – Vol. II Ch. 8

Cricklade – Vol. I Ch. 1

Crowmarsh Gifford – Vol. I Ch. 12

Cumnor – Vol. I Ch. 6

Damer, Anne Seymour – Vol. II Ch. 2

Datchet – Vol. II Ch. 7

Day's Lock – Vol. I Ch. 10

Dorchester – Vol. I Ch. 10

Dorney – Vol. II Ch. 5

Down Ampney – Vol. I Ch. 1

Dudley, Robert, Earl of Leicester – Vol. I Ch. 6

Eaton Weir – Vol. I Ch. 2

Eisey Chapel – Vol. I Ch. 2

Eton – Vol. II Ch. 6

Ewen – Vol. I Ch. 1

Eynsham – Vol. I Ch. 7

Fairford – Vol. I Ch. 2

Fair Rosamond – Vol. I Ch. 7

Faringdon – Vol. I Ch. 2

Folly Bridge – Vol. I Ch. 7

Fulham – Vol. II Ch. 12

Fulham Palace – Vol. II Ch. 12

Gathampton – Vol. I Ch. 12

Gaunt's House – Vol. I Ch. 5

Godstow – Vol. I Ch. 7

Goring – Vol. I Ch. 12

Great Faringdon – Vol. I Ch. 2

Great Marlow – Vol. II Ch. 3

Grove Park – Vol. II Ch. 11

Halliford – Vol. II Ch. 8

Ham – Vol. II Ch. 9

Hamble, River – Vol. II Ch. 2

Hambleden – Vol. II Ch. 2

Harcourt Family, The – Vol. I Ch. 5

Harcourt Family, The – Vol. II Ch. 7

Harcourt, Sir William – Vol. I Ch. 8

Hart's Weir – Vol. I Ch. 2

Hell-Fire Club, The – Vol. II Ch. 2

Henley – Vol. II Ch. 1

Hennerton Backwater – Vol. II Ch. 1

Hoby, Lady – Vol. II Ch. 2

Horton – Vol. II Ch. 7

Hurley – Vol. II Ch. 2

Hurst – Vol. II Ch. 1

Iffley – Vol. I Ch. 8

Iffley Mill – Vol. I Ch. 1, Ch. 8

Inglesham – Vol. I Ch. 2

Inglesham Round House – Vol. I Ch. 2

Isis, River – Vol. I Ch. 1

Isis, River – Vol. II Ch. 1

Isleworth – Vol. II Ch. 9

Jesus Hospital – Vol. II Ch. 4

Kederminster Family – Vol. II Ch. 6

Kelmscott – Vol. I Ch. 2

Kemble – Vol. I Ch. 1

Kempsford – Vol. I Ch. 2

Kew – Vol. II Ch. 11

Kew Gardens – Vol. II Ch. 10

Kit's Quarries – Vol. I Ch. 2

Laleham – Vol. II Ch. 7

Langley Marish – Vol. II Ch. 6

Latton – Vol. I Ch. 1

Leach, River – Vol. I Ch. 2

Lechlade – Vol. I Ch. 2

Lertoll Well – Vol. I Ch. 1

Leslie, G.D., R.A. – Vol. II Ch. 3

Little Wittenham – Vol. I Ch. 10

Littleton – Vol. II Ch. 7

Loddon, River – Vol. II Ch. 1

Long Wittenham – Vol. I Ch. 10

Maidenhead – Vol. II Ch. 3

Mapledurham – Vol. I Ch. 13

Marlow – Vol. II Ch. 3

Marsh Lock – Vol. II Ch. 2

Medley – Vol. I Ch. 7

Medmenham – Vol. II Ch. 2

Milton, John – Vol. II Ch. 7

Mongewell – Vol. I Ch. 11

Morris, William – Vol. I Ch. 2

Mortlake – Vol. II Ch. 11

Moulsford – Vol. I Ch. 13

New Bridge – Vol. I Ch. 5

Newnham Murren – Vol. I Ch. 12

Norreys Family, The – Vol. II Ch. 5

North Stoke – Vol. I Ch. 12

Northmoor – Vol. I Ch. 3

Nuneham Courtney – Vol. I Ch. 8

Oaklade Bridge – Vol. I Ch. 1

Oaklade Bridge – Vol. II Ch. 5

Oatlands – Vol. II Ch. 8

Ockwells – Vol. II Ch. 5

Old England – Vol. II Ch. 10

Old Man's Bridge – Vol. I Ch. 3

Old Windsor – Vol. II Ch. 7

Osiers – Vol. I Ch. 4

Palmer Family, The – Vol. II Ch. 5

Pangbourne – Vol. I Ch. 13

Patrick Stream, The – Vol. II Ch. 1

Penton Hook – Vol. II Ch. 7

Petersham – Vol. II Ch. 9

Pope, Alexander – Vol. I Ch. 5, Ch. 13

Purley – Vol. I Ch. 13

Putney – Vol. II Ch. 12

Putney Bridge – Vol. II Ch. 12

Pye, Henry James – Vol. I Ch. 3

Radcot Bridge – Vol. I Ch. 2

Ray, River – Vol. I Ch. 2

Reading – Vol. I Ch. 13

Reading – Vol. II Ch. 1

Richmond – Vol. II Ch. 9

Robsart, Amy – Vol. I Ch. 6

Runnymede – Vol. II Ch. 7

Ruscombe – Vol. II Ch. 1

Rushes – Vol. I Ch. 4

Rushey Lock – Vol. I Ch. 3

St. Augustine – Vol. I Ch. 1

St. Frideswide – Vol. I Ch. 7

St. John's Lock – Vol. I Ch. 2

St. Lawrence Waltham – Vol. II Ch. 1

Seacourt – Vol. I Ch. 7

Seven Springs – Vol. I Ch. 1

Shelley, Percy Bysshe – Vol. II Ch. 3

Shepperton – Vol. II Ch. 7

Shifford – Vol. I Ch. 3

Shillingford – Vol. I Ch. 11

Shiplake – Vol. II Ch. 1

Shiplake Mill – Vol. I Ch. 1

Shottesbrooke – Vol. II Ch. 1

Sinodun – Vol. I Ch. 10

Smith, Rt. Hon. W. H. – Vol. II Ch. 2

Somerford Keynes – Vol. I Ch. 1

Sonning – Vol. II Ch. 1

Sotwell – Vol. I Ch. 11

South Stoke – Vol. I Ch. 12

Staines – Vol. II Ch. 7

Standlake – Vol. I Ch. 5

Stanton Harcourt – Vol. I Ch. 5

Stanwell – Vol. II Ch. 7

Steventon – Vol. I Ch. 10

Strand-On-The-Green – Vol. II Ch. 11

Streatley – Vol. I Ch. 12

Sutton Courtney – Vol. I Ch. 10

Swillbrook, The – Vol. I Ch. 1, Ch. 2

Swinford Bridge – Vol. I Ch. 7

Tadpole Bridge – Vol. I Ch. 3

Thame, River – Vol. I Ch. 1

Thames and Severn Canal – Vol. I Ch. 1

Thames Head – Vol. I Ch. 1

Thames, River – Vol. I Ch. 1

Thames, River – Vol. II Ch. 1

Torpids – Vol. I Ch. 7

Trewsbury Mead – Vol. I Ch. 1

Turnham Green – Vol. II Ch. 11

Twickenham – Vol. II Ch. 8

Twyford – Vol. II Ch. 1

Upper Somerford Mill – Vol. I Ch. 1

Vicar of Bray, The – Vol. II Ch. 4

Villiers, Barbara, Duchess of Cleveland – Vol. II Ch. 5

Walker, Frederick – Vol. II Ch. 2

Wallingford – Vol. I Ch. 12

Walton – Vol. II Ch. 8

Warborough – Vol. I Ch. 11

Wargrave – Vol. II Ch. 1

Water Eaton – Vol. I Ch. 2

Water Hay – Vol. I Ch. 1

Wey, River – Vol. II Ch. 7

Weybridge – Vol. II Ch. 7

Whitchurch – Vol. II Ch. 12

Willows – Vol. I Ch. 4

Windrush, River – Vol. I Ch. 5

Windsor – Vol. II Ch. 6

Wittenham, Little – Vol. I Ch. 10

Wittenham, Long – Vol. I Ch. 10

Wraysbury – Vol. II Ch. 7

Wye, River – Vol. II Ch. 3

Wytham – Vol. I Ch. 6

~~~

![]()

![]()